POETRY BOY

SHANK, PSYCHOANALYST

Shank was a psychoanalyst — NOT a psychotherapist. Her specialty was analyzing people she had never met. Specifically, she analyzed authors, those who wrote enough to have created a “body of work,” a series of books — sometimes meant to create a “brand” by using a particular lead character or some other device to string the stories together. Even nonfiction writers could be analyzed if they had a special subject, like industrial crimes or office dynamics.

She was not welcome at writer’s groups because her approach was always dissection, cutting, getting down to the skeleton and possibly showing just how rickety it was, or surgically extracting the heart and showing it to the world as mushy or dead. She never admitted that a perfectly healthy author might write about rotten subjects without actually being rotten his or her self. It was an essentially cynical and sophomoric premise but she knew her readers and there were a lot of them. They were not very sophisticated or motivated enough to turn the tables on her.

Anyway, she worked in a particular “space” mostly occupied by the young and a few old hippies who read her for laughs. Her words were formatted in surprising ways — like those old poems in which the subject of a tree was echoed by arranging the words to look like a tree — and interspersed with strange video clips with moving indecipherable glimpses. The whole “body of work” — hers had to be on the Internet because of the clips so it wasn’t a book — was an invitation to projection. She knew this and worked it. Nothing was there — word or shape — without consciousness that the culture had taught most people associations that would make them desire (new cars) or dread (fat).

She was delighted to have discovered, on a back channel provider few people used, a writer she called “Troubadour.” Like her, he used clips that were hard to decipher because they were dark, but his writing was also shadowed. There was no location except that they were always in the debris fallout of civilization — old warehouses where the giant rusted chains swung creaking from high girders and huge industrial fans turned slowly in whatever wind there was because the wall itself was fallen. Or buckled rail lines that curved along cut banks reinforced with cement blocks that had collapsed broken onto the useless steel. Sometimes there was graffiti, often incongruously meant to focus on love and sex in opposition to each other.

The humans — there WERE people now and then, mostly in the distance or as a dismembered part sticking around a corner — either wore black leather or were bare, their flesh almost larval in its shocking pale segmented assemblage. It was sci-fi, humans in an inhuman world, standing before the giant discarded machinery of locomotives and cranes, cables as thick as a wrist, half-unwound from frozen hoists. The sound tracks behind the quotes from existential Cold War philosophers were children’s voices, sometimes telling something and once in a while singing a little nursery song, maybe in French or Spanish or even Chinese.

“Troubador”, she claimed, was an embittered old man who could not find anything good in the world except for his frail memories of childhood which he disguised by using foreign languages. He was one of those power mongers who neglected all his human connections in order to be invulnerable, but was in fact all based on industrialism and when that crashed, he could see only darkness. He was blind to any light in the world, or any hope except the occasional bird that flew too quickly past his view-finder for him to realize it had happened.

She taunted Troubador, which Analytics showed was good for her hit numbers. Everyone loved a fight and was hoping that Troubador would fight back by ripping into Shank. It didn’t happen. Sometimes the most painful act is silence and it appeared that Troubador knew it.

For a while she floated the notion that in fact Troubador had died and his books and posts were now written by his widow. The columns that constantly hoped for trouble and rumours to feed their own productions were “on it” and began to find clues in the major cities of America, because clearly the writing was located there. Then journalists took an interest and the hackers figured out where she herself was, a nondescript apartment near a major university with a good library.

When she had been a student there, she had occasionally fallen into depressions which a counselling service declared were caused by paranoia and borderline personality syndrome. They encouraged her to talk about childhood disappointments and traumas, but in fact she could not remember any. There had not BEEN any. Hers was a very boring suburban childhood in the Pacific Northwest where it rained all the time. The counsellors were either Jewish or Black, either from Manhattan or Alabama and could not conceive of such a place as where she grew up. She ended up parked in contempt all over again.

Finally a journalist tracked her down at the Crepes Suzette Café one Sunday morning and managed to block her from leaving by telling her he knew who Troubadour was and that he lived not far away. She was just curious enough to stay for the information, which he wrote on a napkin. It was a cloth napkin — this was a quality place. She put the napkin in her pocket. The waitperson noticed but didn’t say anything. The critic didn’t carry a purse but only a billfold like a guy. (The journalist wrote that down. He talked about her in his column as a person of “fluid gender” and thus unable to commit or grow where she was planted.)

When she went by the Troubadour’s place, which was supposed to be in the back of an abandoned storefront, all she found was a couple of squatters who ran when they saw her. That night she dreamt that he was there and that they instantly had an affinity she’d never felt before. The dreams persisted and became an ephemeral “body of work” that sort of cut in on her ideas for her daytime paid work. That was inconvenient but not deadly since she had a good bit of money in the bank. Some of it was from agreeing not to analyze certain writers.

The vid clips in her dreams were somewhat clearer than the ones she made in real life for her critical blog. There began to be mirrors and someone moving past them. Maybe it was Troubadour. At bedtime she encouraged herself to stop and focus on that mysterious figure, hoping her subconscious would pick up on the request.

It worked. The camera stopped, the figure turned — she hardly recognized the person. It was hard to take it in. There was no Troubadour. The person she saw in the mirror was Hacker, herself. She told no one. She moved to a small town in Arizona and became a librarian. In that town no one thought she was mysterious at all. But at night she was still Hacker/Troubador — she just didn’t record any of it, not even to write it down. It passed through her consciousness unrecorded. Daytime sane/nighttime psycho. A classical pattern. She enjoyed talk shows that tore people apart and watched them on YouTube while she ate breakfast, smiling into her coffee mug.

BACK COUNTRY FAMILIES

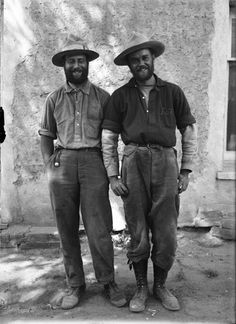

Milt and Hup were very tight in that classic way of buddies that sometimes develops between men in combat. They hadn’t been in combat together, but they both saw life as hostile and out to get them, so the feeling that they had each other’s backs was strong between them even though Milt was old enough to be Hup’s father but wasn’t. Instead he was Hup’s father-in-law.

So Hup had married Milt’s daughter, Giselle, in order to have a formal, legal relationship to Milt. He didn’t really love Giselle, but then he didn’t really love any other woman either. The kid heard about all this with horror. He’d gone to sleep behind the sofa where he’d been reading until his eyes got tired. It was a good place to lie on his stomach where people wouldn’t step on him or spot him and think of something for him to do. His mother was confronting his Aunt Theda, Hup’s sister so Milt’s daughter. The two of them were shouting in a rage, but not quite at each other — rather at the injustice of life that refused to obey any kind of proper order.

“You know it’s true, Giselle. It’s like my dad just gave you to Hup, his possession — men own women. It in the goddamn wedding vows.”

“It’s perverse. It shouldn’t be. I’ll leave him.”

“You can’t. You have no money, you have no skills, you have no close friends to help you. You are trapped, honey, and I can’t help you because I’m in the same situation. That’s the way it is here in this back country.”

The kid hadn’t thought of this as “back country.” To him it was the center of the universe, it was home, there was no other conceivable place. Neither could he understand why it was wrong for two men to love each other, two men he also loved in the world. The only man he loved more was his father’s father, Papop. Milt and Hup were subsistence hunters because that was how one survived in this rural place, but Papop was a fisherman and since the farm was bordered on one side by a river, he and the kid would walk down together and almost always return with a stringer of fish. He didn’t even mind cleaning them. It wasn’t like the bloody sad work of gutting animals.

The men of the farm were a fierce lot, knotted up with the necessity of work and the danger of not calculating some kind of risk, whether from the prices or from weather. They didn’t keep many animals, so there wasn’t so much risk from bulls or boars. They WERE the bulls and boars. They called the women “hens,” and roosters made them laugh, esp. when the feathered ruffians fought for dominance.

Very rarely did the men take the kid hunting. They said he was noisy and couldn’t think like a deer. But they were wrong. He often practised following the vague deer trails around the farm, through the woodlot and the undeveloped land beyond their boundaries. When he glimpsed an animal, he slipped along behind it, watching to learn what it did, not intending to interfere.

He was even better at understanding fish. It may have been because he was an excellent swimmer, but somehow he understood water, its dynamics and power. He could imagine hanging in a quiet spot behind a boulder or along the bank, but he also sensed the rush of narrow places and waterfalls. He liked “rush”. When he grew older, it would become a problem, a drug problem.

But now he just loved most going with Papop on his canoe, floating quietly along through the sun-dappled river under the arching trees and not even saying anything, because fish can hear, you know. It was the walk back to the house when they could talk. “Papop, did Grandpa Milt really give my mother to Hup?”

“Well, that’s the way it’s been done for centuries, boy. And then she gave you to him!”

“Does it mean Hup loves Grandpa Milt more than my mom?”

Papop had a pretty good idea where the kid got this idea. Those damned women were always fomenting discord, always trying to grab attention by confronting. Why couldn’t they just bake pies, get a little praise for it, go to church?

“There are different kinds of love.” The kid could never get much more out of Papop. He could feel that there was a whole lot more to be said.

“If Milt owns me because he’s my father, do you own Milt?”

Papop laughed bitterly, but he wouldn’t answer. Then they were back at the house, almost late for supper. At the last minute Papop muttered, “Nobody owns Hup.”

None of the men was much good at vegetable gardening. The women refused to do it. They wouldn’t even grow flower borders. So the kid got to do the honors. Hup did the basic digging and planting, but then he handed the kid a hoe. “Keep it sharp,” he said.

So the kid did until he accidentally chopped his foot — not very seriously, but it infected and made him limp for weeks. Papop showed him how to soak it in a bucket of salt water. Hup said the kid’s limp was psychological, to get out of work. Milt agreed that work was everything, work was survival, work was food. They told the kid to stop dreaming and pay attention. The women stayed out of it.

The kid certainly was a dreamer. Even his school teachers said so. They didn’t know that the storm of attempted sorting in his head over the women’s family quarrels and the men’s tough attitude about “manliness” was sometimes making him almost deaf and blind. He went to the library and read books, because it almost helped. He read Hemingway which did help and tried Faulkner, which didn’t. He didn’t know about Steinbeck. Then one day he found Whitman. He had found his heart. The others didn’t matter now.

Even when his aunt and mother had another fight over whether or not he might be gay, he didn’t care. The poetry of Whitman sang in him through every fiber and breath.

When his Papop died in his sleep (heart) the dynamics of the farm life were irrevocably changed along with the inheritances because now Hup owned the farm. None of them had realized how Papop’s quiet presence had been a calming and a constraint on these two belligerent men. Hup had never dared smack his wife and son around until Papop was gone. Milt pretended he didn’t know.

The kid, who was growing quickly by now, heard his mother screaming one last time, took his fishing rod, and his Whitman book, and left in Papop’s canoe. Teach a boy to fish, and he can feed himself. Of course, the rivers were clean in those days. But there are always men who read “Leaves of Grass” and he found them.

CONVERSATIONS WITH TWO MEN

My usefulness as a counselor is pretty limited. I listen carefully and am a pretty good analyst, but when it comes to the part where you’re supposed to give advice, I never have any idea what they should do. At least no idea any better than their own notion of what action to take, if any. Actually, sometimes I do, but it’s usually pretty harsh. Most people are not looking for more pain. They just want to be heard.

But I do have a little niche, which is as a sort of confessor/ confidante for a certain kind of man. They never see me as sexy, which may be a qualification, and they don’t want me to tell them what to do. They just want me to listen carefully enough to understand. It has something to do with the fourteen-year-old boy in me, who really wants to know these things. Even in high school when I was actually fourteen, real fourteen-year-old boys wanted to tell me things about themselves. In college it was often via letters — one roommate had had a nerdy friend in high school who went to a different university and he and I wrote back and forth for a couple of years, mostly about sex — you might suspect we were both nerdy virgins.

After I became a minister, it was a vocational duty, but I soon learned to avoid women who came with bad motives, like trying to intimidate me with their pasts or to ferret out secrets about my own past. The men treated me like an equal. They just wanted to tell me things quietly. No brags, no anger, sometimes rueful regret.

Twice, men told me about finding their ex-wives dead, eerily echoing each other though they didn’t know each other. They had divorced late in life, after the kids were all raised and having their own kids. The wives had not asked for divorce but didn’t really fight it either. In fact, I had spent time with one couple, working out the reasons, the sensible way to separate, and a kind of description of the future. Both women accepted support and the men didn’t promise anything beyond the legal agreement, but in fact were pretty conscientious about stopping by now and then to make sure everything was all right. Often they left more money. They seemed to become something like siblings.

One couple had sons, who also stopped by, and the other had daughters, who did not. I think the difference was not in their personalities, but in the social gender roles in which the males were still made to feel responsible but the females thought women could cope on their own. They were not comfortable when their fathers found other women. Their mothers didn’t date. They were generous babysitters.

In the end, one woman’s friends from her church called the ex-husband one Sunday morning to say she hadn’t showed up, which was unlike her, esp. since there was a meeting she chaired. She wasn’t answering the phone. They were thinking her car might have failed, so she would need a ride. The man went to her apartment where the super, who knew him, let him in — just unlocked the door but didn’t stay. The ex called out and got no answer. When he went to the bedroom, there she was, on her back, naked and wet, with a towel in her hand. He said she looked like the girl he had married, all lines erased, slightly smiling. She still had her figure. Her doctor said a heart attack when emerging from the shower, a sudden death that tipped her over onto the bed. The doc said she’d known it was possible but hadn’t told her ex-husband.

The other man wasn’t called close to the time of death. His wife lived in a trailer and the neighbors became concerned when they didn’t see her for a few days. She had begun to drink a few beers in the evening — actually, they had always been people who had a few drinks with dinner. He had to wrench and jimmy to get the door open. She was sitting in front of the television set, which buzzed away as though her eyes were still seeing the picture. He half thought that when he switched off the television, it would cause her to be living again. There was no real diagnosis.

Neither man wept as they spoke to me. Probably they shed more tears at the time of the divorce. The reactions of their children had been various, each according to his or her temperament, more about them than about the marriages of their parents, but neither set of sibs had really known much about the parental relationship. Didn’t know their fathers very well because of them working so much, and focused so much on escaping their mother’s expectations that they didn’t know them much either.

Which was a shame, because the two pairs were charming, intelligent people who had begun their families with real joy and competence. Somehow the world changed and that changed their relationships. Now the new sexual code would have allowed all of them to seek adventures. The men wanted to, but the women didn’t. The men had tried to be honorable, ending their marriage before looking around. They never did meet each other, though I was friends with both. Neither was in my congregation. One was a breakfast buddy. The other often volunteered to drive me when I went to a conference in another town so we’d have a chance to talk in the car. He’d explore that town and pick me up afterwards. No one ever suspected me of having affairs with these men and I didn’t.

One would think that there might be some difference between the two men. Maybe one was more inclined to use Viagra than the other, but both were genuinely looking for intimacy and personality — not just sex. We didn’t talk about sex. They didn’t seem to feel guilty, but rather groping for some understanding about what a human life really means in the end when we can die so suddenly — just be gone. They did feel a little relieved about no longer having a kind of undefined financial responsibility. One wife had asked to be cremated and scattered. The other had a proper funeral in her own church.

By the time these men died, I had moved to a different city half across the country. Someone sent me a clipping of the newspaper obituary for one. I didn’t know until years later that the other had died. The conversations I had with them — actually, me only listening — come back to me at unexpected times. The issues remain unresolved. Unresolvable. I’ve never talked about them until now.

TWO VERSIONS OF THE SAME THING

William Schulz: “Liberalism in Theory and Praxis”, the title of a speech, appears to be the source of the following notes in the pile of stuff I’m sorting, but when I googled, this is what I got: https://wikileaks.org/podesta-emails/fileid/48374/13442 The content was Schulz’s vita. Very mysterious and suggestive. You don’t need his vita.

He’s a UUA leader, quite charismatic, sometimes a bit Luciferan exp. around women. Called me at 3AM once when I was circuit-riding in Montana to see whether Alan Deale was thinking of running for president of the UUA. Luckily for him, it was the one day a week I slept in my apartment instead of my van. Unluckily, I was not as much of a confidante of Deale as Schulz thought. I didn’t know.

Anyway, wherever the notes came from, here they are:

The challenge of the 21st century will be to redefine liberalism and humanism in light of the discoveries of “new physics.” We must accept the totality and the indivisibility of the universe, and abandon the demand of the human ego to somehow be special or separated from the rest of the cosmos.

5 new UU affirmations

1.The wonders of the cosmos outspill every category into which we try to fill them.

2. The cosmos is all of one piece.

3. The future is in human hands, but only a global consciousness will do.

4. Only the earth itself deserves our loyalty.

5. The gracious is available to every one of us disguised in the simple and mundane.

Instead of commenting, I’m going to summon up a little story.

_______________________

A small campfire burned on the high SW desert ridge. An old man hunched on a camp stool. His beard was trimmed but his white wavy hair was long and pulled back into something like a bun. The fire sighed and shifted as though it were alive. The two young men, old enough to drive but not to vote in some states, watched it almost suspiciously. They were city boys, suspecting it would jump up and run away through the pinon and juniper.

One boy was teaching himself how to play a kazoo, a plastic toy, really. Some people might think it was a drug pipe of some kind, but it was innocent as paper wrapped around a comb. The other boy was smoking Marlboros, thinking about cowboys, and the threat of cancer was minor compared to all the other dreads and dooms of his life. Infections, traumas, and intermittent moments of ecstasy and glee, many of them sexual. Sometimes monetary.

He addressed the old man, who often talked about death these days, maybe self-immolation, something dramatic that would make a point, take a stand in a meaningless world. “You SAID this would be a remote place, but WTF!!”

They were looking from so high and far, through air so thin and cold, that they could see the horizon curve, just bending a little bit, gracefully. All three were acutely aware — because they liked sand war movies — that satellites could focus in on them, pick up not just the light of the campfire but even the glow on the end of the cigarette. They could at least be recorded but probably not bombed by a predator drone because the cost to benefit damage just wouldn’t compute. Still, it made a nice edge to awareness.

In the dust near the fire the two dogs groaned and turned over a bit. They loved the campfire heat. And it had been an exciting day, a lot to dream out into sense memories — the smells alone…

“Are we all gonna sleep in the jeep tonight?” asked the kazoo man.

“I am,” said Mr. Marlboro. “I’m afraid of snakes.”

“We’re too high for snakes,” murmured the old man. “Might be visited by a cougar.” He grinned. The boys exchanged looks. Then they relaxed a bit — the dogs.

When they got closer to sleeping, the youngsters went to the edge of the ridge and made high amber arcs out into space for a surprisingly long time. The old man didn’t join them. He didn’t like comparisons, but the two young ‘uns were happy rivals to each other. The acrid smell of male urine joined all the other pungencies of the smoke-laden air. When they climbed into the jeep, the springs bounced for a while.

Arranged in his bedding, he smiled. The tracking satellites intercepted the single stars and the Milky Way and he thought back to other times he’d visited this place on some vision quest or need for whatever it was he found here. The first time, it was he who was the boy, but he carried a harmonica in his pocket and had known how to play it since he was almost a baby. He could chord and phrase in a way that made the ladies cry.

As if he cared. Ladies always find something to cry about. But he always had a dog and the dog always liked the harmonica, sometimes sang along with it, sometimes between the two of them calling in the coyotes, but never a wolf. He would have liked to have heard a wolf out there in the silver-lined darkness, but that early time he and his old man were on horseback, so it was just as well.

He wouldn’t sleep tonight, not use the flask of whiskey. He’d doze rocking along in the back of the Jeep while the boys argued their way down off the ridge and on to the next destination, which was the Pacific Ocean. They’d never seen it. Poor deprived kids. He’d show them he still knew how to body surf.

He’d been reading physics lately, different from the kind of physics he knew in university, which was so solid and clear. Now it was practically religion, full of images of ambiguity, but somehow reassuring — always changing but never ending, even if you got impatient and gripped Time to tie a final knot in it. The dogs, now that the fire had died down, came over to sleep against him, one on each side. He turned onto his side so one could have his back and threw his arm gently over the other one. Their tails wagged for a moment and then they went back to sleep.

BALTHAZAR

Balthazar was a unique guy. But he was also, paradoxically, double — almost multiple — but capable of major arguments with himself from both extremes of the possible positions at once. He had this exotic name though he was from a small midwestern town where his father was a prosperous and respected banker but his mother had a lot of pretensions about Arabia, which she didn’t seem to realize was not a real place — just a concept. I saw her photo and she DID look Arabian. I mean, like someone out of those paintings of harems with sumptuous marble and fountains. But he said she dyed her hair black.

Actually, she read the books of Laurence Durrell over and over. Also, his friends — who were even more louche, if that were possible. She said they had imagination and daring. She had the imagination, but wasn’t very daring. Her husband was able to keep her out of trouble. Chemically, if necessary.

Not Balthazar. I met him at the Louvre in Paris. I won’t tell you which painting we were confronting, but we began to talk and were soon so emphatic and hilarious that we were asked to leave. We continued outside while dodging the bicycles and skateboards, hardly noticing them even as we avoided colliisions.

After that we often met. Balthazar took me in hand. He insisted that my jeans and plaid shirts were boring and predictable. We went shopping and he chose leather trousers and a scarlet velveteen shirt — things I NEVER would have bought for myself. When it was time to pay, he had already gone on to a little shop across the street so I used my credit card. He promised to reimburse me, but I didn’t let him, since I was the one wearing the clothes and I started getting compliments right away.

One afternoon he decided to give me a haircut that was almost shocking but sort of went with the clothes. It was very short except that he left a forelock flopped over my forehead. In a while I learned to manage it. Then later he decided I should have a pierced ear and installed a little gold hoop that I was supposed to twirl every day so the hole would heal open. It was healed soon and he brought me an ear rim cuff to go with a proper pend d’orielle, rather elaborate and dangling.

A new daring restaurant opened that had curtained alcoves that were meant to look like tents. The food was Moroccan, very expensive. The point wasn’t the food anyway — one was really paying for the seclusion and the status of what was implied. We arranged to meet there and Balthazar even ordered the menu in advance, but it wasn’t very secluded because I kept one of the “tent flaps” swept back in order to spot him when he came, which he didn’t. There was some kind of emergency, but I’m unclear about what it was. The explanation was kind of complicated. Again, he offered to reimburse me for the meal, but I had eaten some of it, so I said no.

I really wasn’t old enough to raise much of a beard, but Balthazar gave me a proper barber’s treatment with the hot towel and lather with a brush and even used a straight razor, which was a bit of a thrill. He did manage to define a mustache and sideburns and used a little coloring on them. Then he wanted to line my eyes, but I thought that was going too far. Already I was attracting flirtations on the street. But then, it WAS Paris.

One day he suggested we meet at a bench on the end of a pier looking out over the sea in a deserted part of the shore where no one would mind if we slung an arm over one another’s shoulders. He said I should take a hired car out there and wait for him so we could watch the sun go down together. It did go down, but he wasn’t there.

I sat for a while in the failing light, thinking about why Balthazar was like that. Some people say it’s organic, that some people are born with two minds in one brain. Others say it’s the result of terrible trauma, a kind of dissociation that happens under extreme duress and can actually cause personality to split into new constructs. And there are always the people who claim narcissism is at the root of everything and say he just never considered that other people might have needs and desires.

Of course, I examined myself as well. Why would I continue to admire Balthazar, who by now was dressing all in black like a gunslinger and was arguing with me unfairly, about things I never claimed? Why did I continue to attend his rendezvous ideas, even though they left me holding the “bag”— meaning the bill. It felt to me like love, as though I would do anything to be with him. Our other friends had wandered off, feeling superfluous and ignored, so I was almost with him by default. Was I playing the SM game? Of course, I was. Everyone does. Put any two people together and one will be dominant, simply because of being stronger or smarter.

A seagull came to visit me on that bench but didn’t stay long. Pretty soon it got dark out there. I decided to walk back to the city. I don’t carry a cell phone so it wasn’t much of a decision, more of a choice not to spend the night there.

On the way back, walking along the highway, I accepted a ride from three guys. It was a mistake. They treated me very badly indeed, left me blooding from all orifices, including the hole in my earlobe when they tore away my pend d’orielle. They took my fine clothes but left my hank of hair hanging over my blackened eyes. I was unconscious by then. I don’t know who brought me to the hospital or why no police have come to interview me. I woke with a sense of deja vu.

The doctor prescribed me some pills. He talked gently about being bipolar and all that sort of thing. He must have found out who I was because a friend brought some of my old jeans and shirts. It wasn’t Balthazar. I never saw Balthazar again. At least not in the way I had. When I finally had access to a big mirror, I realized the truth.

Balthazar, c’est moi.

“MORTALITY AND ART”

His girl friend, inevitably a couple of decades younger but keeping company with him — because at least he was “het” — was quite different. Neither tomorrow nor a year meant anything to her. There was right now and there was eternity. The rest was up for discussion, or rather, argument. She fought with time, but both of them knew that was nonsense, a waste of energy.

“I’ll die long before you do,” he said.

“You don’t KNOW that! I might get run over by a truck tomorrow!”

“No truck would dare.” She hit him with a pillow.

Behind her back he began quarrelling with all his friends to get rid of them because he had the deranged idea that it would be easier for them to bear his death if they were angry with him. It had always worked that way for him. If he wasn’t already mad at them beforehand, he got doubly enraged when they died without warning him, without asking him. It was surprising — almost, but not quite worrying — that it was so easy to run them off. But cynicism had always helped him cope and it did not fail him now.

No, that’s not the way it was at all. That’s not honest. The truth was that he needed help and she was just enough compliant with the gender role stereotype to provide it. He was a painter and the paintings didn’t sell all that well, so in the end — if she could stick it out — she would end up with the paintings. His agent was very aware of this dynamic and watched her carefully. But no one could get the artist to draw up proper documents to make a guide for justice, fairness, contingency. He said, “Whatever happens, just happens.”

She painted her own works and there was a possibility that because of her closeness to him, her work would pick up value, like something sticky acquiring lint. She hated that thought. She hated all thoughts, but she lived by thinking.

Sometimes she hated him as well; certainly his agent. That older woman had a fetish for very high heels until she had broken her ankles so many times that she began to wear boots, high boots — not high heels, but high leather uppers, to hide steel braces inside them. Then she discovered cowboy boots and wore them with long denim skirts. This became the agent’s trademark. A mockery of something that was once real work done in the dust. At least that’s what he said, to be cynical.

Suddenly he fired that agent and the companion was both relieved and a bit worried. As she had feared, then he turned on her. What did it mean? Late stage dementia? A desire to spare her grief (though, of course, it only compounded sorrow, gave it a sharp poisoned tip).

Then she noticed shadowy figures slipping into the studio. They seemed to be male and rather young, but she didn’t recognize either customers or fellow artists. Casually dressed, faceless. When she asked, he denied they even existed. And when she objected to the way he was treating her, he wept and said he needed her. Couldn’t make it without her. But if he was going to die anyway, what did “make it” mean?

Was he covertly gay? She wouldn’t have cared except that she didn’t know that language, those social rules. When she consulted a gay friend, he said it didn’t seem likely.

Was there some kind of criminal connection? Dangerous people? She slipped into fantasy and thought maybe the figures were his past selves, his young selves. She knew a lot about them from his stories, so maybe it was HER fantasy, not his at all.

Some artists keep a secret body of work, like Wyeth painting and painting that neighborhood woman, trying to do something inscrutable, which society assumed was about sex because they always assume that, but which may have been something else, like mortality which the woman was sturdy enough to embody. The companion looked, but did not find, a secret body of work. Was she herself embodying mortality? Is that why the subject of their arguments was often who would die first?

She sometimes said that she had the power to keep him alive forever simply by remembering his life and by “curating” his work, pointing out the best and explaining how and when it was created, the incidents that led up to the paintings, their embodiment, so to speak.

He said this would destroy him. That one who looked at his works should only respond with the whole self, that it was dishonest to prompt viewers and lead them to expect certain things. In fact, that could destroy his whole career by limiting the framing of it to the opinion of experts since experts shift, argue against the just-previous expertise, and discredit whole categories of work. Most people are afraid or even unable to react in a thoroughly genuine and unique way. Every time his work was confronted by an honest person with real reactions, it was renewed.

She said this was cynical. He shrugged. She said he was still interpreting everything in terms of his youth, that revolutionary period of the Sixties and Seventies. He pointed out that he wasn’t even a painter then. Not even BORN. She screamed.

In the end it was all very prosaic. He died in his sleep. She went home with one of his best friends and in their hurt and loss, they forged a new intimacy that included the painter. It turned out that the shadowy figures were his sons by a very early wife he’d never told her about. She never could find a painting of that woman and neither of his sons painted or would talk to her. One night she went by the studio and found everything gone. She assumed it was the sons.

Without their assistance or permission, the companion and her new partner wrote a book about the painter that was highly influential, much respected because of its “Truth.” It sold moderately well.

GLAMOUR GRANNY

She had been suicidal all her life. If she had spoken of it to anyone, even herself, she would have said her subconscious or maybe unconscious was trying to kill her. She was never sure why, but well aware that one never entirely knows one’s own deep dark interior, though she had always found sin to be alluring. She neatly made it not her fault but not anyone else’s fault, an eerie compromise between her intentions and her victimization. She didn’t want anyone else involved, but she liked it there on the threshold, going back and forth.

And that’s where she had lived since the accident broke her back. It was a banal incident — she had fought with her husband, gone off in her flashy little car and, blinded by anger, drove over a cliff. They didn’t find her for a day or so because she couldn’t be seen from the road. She was unconscious during the rescue and only woke up in the hospital, resentful at leaving her dream world for this other place of pain and demands where the only good thing was the pain meds.

She also took steps, devised little strategies, to avert any actual suicide attempts, though now that she was in her eighties and widowed, living in a wheelchair, the flirtation was beginning to be serious. It was necessary not to tip her hand. (She had been as good a card player as dancer.) Since she had caretakers, the obstacles were also stronger.

At the moment she could hear Clara Marie, her part-Chippewa helper, rustling around in the kitchen and then the sound of the boy’s voice. The grandson was what she lived for: his dimples, his flashing eyes, his wild ideas. He was quite different from his father and she could not see how he came from such a plodding mother.

The boy often brought her small gifts: a peacock-colored scarf, pearl earrings, a magazine folded back to a Blackglama ad because he thought of her that way, looking out over a ruff of fur with painted eyes. She told him tales about better days when she had been the most popular dancer at the ball, so many swirling dances with so many handsome men. When she dozed, which she did often, the ballrooms where she had worn fine gowns and real diamonds mixed with the dances in the old movies that she watched on television. Lost in the lovely oblivion she danced among the clouds and stars, mixing history and places between Anna Karenina and Ginger Rogers. If she were lucky and had enough pain meds, she’d only return to reality late enough in the afternoon that the boy might be there.

This time she thought she heard two male voices in the kitchen talking to Clara Marie. Impatiently, she rattled her wheelchair to remind that boy she was waiting. When the door to her bedroom burst open, there were two boys. It took a moment to understand because this boy was dusky and black-haired like Clara Marie but she had no young sons, just girls and more girls, all destined to take care of others.

“And who is THIS?” She held out her arm, half-reaching and half-pointing. Laughing, the young man, bowing, took her hand and kissed it! She was immediately smitten. It was a long time since that had happened.

“Grand-mére, this is my best friend! We’ve brought you a gift!” It was a small tape player, what they called a “Walkman” and it had a small headset which the boy put on her. “Be careful. I don’t want my hair messed up. Just because I’m only sitting here doesn’t mean you can play with me. I still have my standards!”

Claude Francois (that was his name) turned on the little player and she was surprised to hear dance music, HER kind of dance music, playing through the headphones as though the orchestra were right in her head. She could not help smiling. The two young men grinned at each other and then took each other in their arms in the waltz embrace. They didn’t need to hear the music to keep the beat and she raised her own arms as though she, once again, were leaning against an immaculate tuxedo, wearing a full-skirted but low-cut dress, moving round and round so quickly that her long flashing earrings swung out from her neck.

Dark Claude Francois and her golden grandson were perfectly matched in height and synchrony and for a moment were locked by their gaze. Then they saw that she was swaying her arms and — keeping the step rhythm — came to each side of her chair. Now they moved her around the room, which was carpetless for ease in rolling the chair, and it was like actually dancing, a three-some this time. She caught glimpses of them in the big dressing table mirror as they passed and they were splendid. All three laughed and laughed.

Then they were panting and had to stop. It was time for them to go. She kept her dignity by being stoic when they kissed her cheeks, forbidding herself to smile for fear of it becoming a grimace. When the door had closed she ripped off the headphones without regard for messing up her hair and threw them across the room, which dragged the little player along, clattering. She heard the big motorcycle fire up and roar away.

They had not quite had to courage to tell her, but she had sensed what they were going to do, so she was not surprised when later Clara Marie remarked, “Those boys will be happy in San Francisco.” How could she begrudge them their freedom? She herself did not intend to stay.

THE KEEPER OF SECRETS

The boy had become the family Keeper of Secrets. He was smart and listened well, so that seemed natural, but the family was large and had a lot of traditional women in it — that is, women who had things to say, but no one listened to them. So they told the boy. Also, these women were often rivalrous so they tended to see many little faults in each other, but particularly between the two branches of the family, the paternal and maternal. He didn’t call them that. He said, “City family, country family.”

His mom was country family now but she was city family before she married his dad. It was hard for her to learn how to be country and her sisters could never understand why she married into such a situation, though they liked to visit now and then, if only to inform her how much better their lives were. Then they’d get the boy off to the side and pump him for information about his mother and father.

He was a good secret keeper and learned early which ones were radioactive and which ones had such obvious and dull answers that they were safe, though he was careful to leave out details or add ones that meant nothing, just to disarm the information. The trouble was that as a little boy, he really didn’t know the difference between dangerous and innocent and once in a long time he would trip up and hear things screamed at his mother. Things like, “How can you neglect your hands like that? When was the last time you had a decent manicure?” He didn’t know what a manicure was.

The main secret he didn’t know himself was that being a little boy meant that he shouldn’t have been told many things. Not until he was an adult did he understand that miscarriages, abortions, lovers, early menopause and a host of accusations like “mother always loved you best” were not for little boy’s ears, much less any expectation that he could figure out what they meant or what to do about them.

Once he went to his father to ask what some of these things meant, but that was a mistake. His father lost his temper easily and was likely to react violently. Not that he didn’t slap, grab, and shove both he and his mother all the time anyway, sometimes hard enough to bruise and once or twice violently enough to break bones. Even if he went to school with a black eye, it was evidently a secret not to be mentioned by his teachers or classmates. He knew never to tell home things at school or school things at home.

The grandmothers hated each other. His paternal grandmother dearly loved and praised his father, her cherished only son. His maternal grandmother had no time for boys or men. This may have been because his maternal grandfather had disappeared, taking the family dog, and left her to raise all the girls alone. Most of them worked hard at school and jobs and were successes, but didn’t marry except for his mother.

So he formed an alliance with his paternal grandfather and the two of them became prodigious fishermen. Glam told him everything he knew about fish — which was a lot — but when the boy asked about his parents, the old man confided that he didn’t understand women and, frankly, he was afraid of his own belligerent son. With reason. His son had once actually punched him out. He explained it was wrong to go to the police when your son knocks you down. It was a city thing to do.

There were a few boys at school who had families that were similar. It was the way of the world to push fathers into these roles, criticizing them if they were weak or talked too much or didn’t make enough money. Love was a luxury or a material obligation like chocolates at Valentine’s Day.

The country was rapidly developing as more housing was needed. But there was still enough undeveloped land around the farms for the boys to find places to gather, even to build a little campfire and gather around it. They didn’t roast marshmallows — these were boys who kept dried beef jerky sticks in their pockets to chew on when necessary. The “hotter” the better. Not that they wouldn’t accept cookies when they were offered, but they tried not to mention that or to ask for them.

They didn’t discuss their families much because it would be complaining, but sometimes a boy caught in a domestic war would spend some time cursing and imagining terrible retributions. Then one day an uncle showed up, a not-quite-grownup who seemed very worldly. One of the comforts of the boys was smoking, which was in the comfortably gray area of disapproved and risky but not really illegal, and easily broken down for sharing, one at a time from a pack or handed back and forth, with the little added element of being a kind of displaced kissing. Nicotine was both arousing and calming. It helped with the anxiety and the smoke was fun.

The uncle, who was quite a bit younger than their parents but older than the boys, asked them if they ever smoked pot. The boys were still pretty young and they had not, but they knew what it was. He had some with him. Some say pot is a threshold drug and will lead up the primrose path to heroin and so on, but the real threshold drugs were the self-generated hormones of sex and worry. And the real addiction was secrecy.

The uncle had been in the Navy and the reason he left was a secret. One summer day he invited one of the boys to walk with him away from the group to a wooded place he knew because he “wanted to show him something.” It was sexual and began as seduction but ended as force. Rape, to give it the right name. The boy yelled and the other boys came. They weren’t in time but the uncle did not escape.

It was a wooded place because there was a spring and that kept the ground wet and soft. They buried him there and his remains disappeared quicker than one might guess. No one ever told the secret and because of the spring that land wasn’t built on for decades. The uncle’s sister, who was the mother of one of the boys, grumbled, “I understand that men always leave, but he could have taken his worthless dog with him.” The boy loved that dog.